Web Content Display

Web Content Display

Honoring the Achievements of FDR’s Secretary of Labor

By Jessica Breitman, SUNY New Paltz, FDR Library Intern

To commemorate Women’s History Month, the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library honors Frances Perkins, FDR’s Secretary of Labor and the first woman appointed to a presidential cabinet.

Foundations in Economics and Labor

Born in Boston to well-educated parents on April 10, 1880, Frances Perkins attended the women’s college Mount Holyoke, founded by Mary Lyon, a pioneer in women’s education. Lyon’s empowering adage to the young ladies at Mount Holyoke was: “Go Forward, attempt great things, accomplish great things” (Downey 11). Although she majored in both chemistry and physics, Perkins was always fascinated by her economics electives and began developing the necessary tools that she later would need as Secretary of Labor. She visited factories, interviewed workers and took notes on their wages, hours, and working conditions and learned the cold-hard facts of industrial life.

Nested Portlets

Nested Portlets

Web Content Display

Web Content Display

In 1907, she moved to Philadelphia, where she became the general secretary of the Philadelphia Research and Protective Association. Her job investigating phony employment agencies that preyed on immigrant women put her face-to-face with pimps, drug dealers, and other criminal elements. While in Philadelphia she enrolled at the Wharton School of Finance and Commerce at the University of Pennsylvania, in an effort to expand her knowledge of economics.

After two years she moved to New York City, confident that she had gained enough experience to acquire a job helping the less fortunate. She moved into a settlement house in Greenwich Village, attended Columbia University working to obtain a graduate degree in political science and became heavily involved in the women’s suffrage movement. She advocated for women’s rights on street corners, protests and in meetings.

Web Content Display

Web Content Display

When approached about working for the National Consumers League, Perkins jumped at the opportunity, eager to work for an organization that advocated for worker’s rights and protection. There she got her first taste of politics as she lobbied for the elimination of child labor and for the creation of a shorter workweek. In 1911, she invited President Theodore Roosevelt to attend a league meeting in New York. Although the President declined her invitation, this marked the beginning of a growing reputation in the world of politics.

Web Content Display

Web Content Display

Web Content Display

Web Content Display

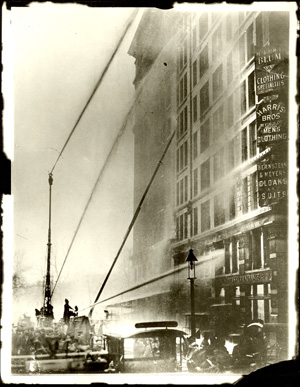

On March 25, 1911 the notorious Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire occurred in New York City. Frances Perkins happened to stumble upon the horrific scene. The factory employed hundreds of workers, mostly young and impoverished women. As a result of poor safety regulations, such as faulty fire escapes and locked doors, the workers could not escape the scorching fire. One by one desperate women jumped to their deaths from the upper floors of the factory. 146 workers died that day. Perkins immediately took action and sought ways to prevent future workplace tragedies. Recommended by Theodore Roosevelt, she was named executive secretary of a Committee on Safety. The Committee was instrumental in creating the New York State Factory Investigating Commission, a legislative panel that investigated factories and other workplaces and make sure they were up to code.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

In 1929, New York State Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Frances Perkins as the Industrial Commissioner of the State of New York. FDR recognized her intelligence, wit, and no-nonsense attitude and knew she was right for the job. She took full advantage of her new position to help the impoverished.

When the stock market crashed in 1929, Perkins persistently encouraged FDR to take action. FDR became the first American governor to stress that unemployment was a major national problem (Downey 110). He created a committee on employment, and appointed Perkins to be in charge. She traveled to England to study their unemployment compensation program in order to construct a similar program in the United States.

In January 1930, Ms. Perkins made news when she publically contradicted President Herbert Hoover about the severity of the nation’s economic and unemployment problems. FDR admired her courage. The admiration was mutual: “Frances saw that Roosevelt treated her as a peer, and in return she devoted to him her skills, diplomacy, and remarkable emotional intelligence” (Downey 303).

Web Content Display

Web Content Display

Department of Labor

When FDR was elected President in 1932 there was speculation over who the President would select for his cabinet. One name that kept coming up was that of Frances Perkins. Because no woman had previously served in a presidential cabinet, any woman appointed would be closely scrutinized and be targeted for criticism.

Impressed by her ability and accomplishments, President Franklin Roosevelt offered Frances Perkins the position of Secretary of Labor. As Secretary of Labor, Perkins took on the responsibility of developing solutions to the problems being caused by the Great Depression. Most pressing was the fact that between 13 and 18 million Americans were unemployed (Downey 149).

The first public works project created by the Roosevelt administration was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which provided unskilled unmarried men manual labor jobs in the conservation and development of natural resources in rural lands owned by the government. Her political and administrative support made the CCC one of the great early successes of the New Deal. She also worked long days to battle unemployment, and garner support for the New Deal and other programs, and in 1933 alone, she gave more than a hundred speeches.

Web Content Display

Web Content Display

Social Security

Perkins’ most significant contribution to the New Deal was, of course, the Social Security program. Franklin Roosevelt was the first sitting president to support government-sponsored old age, unemployment, and health insurance. FDR wanted to enact a national program to address the broad problem of economic insecurity. But he recognized he would face political, economic, and constitutional challenges.

Taking office at the lowest point of the Great Depression, the new president chose to delay tackling long-term economic security as he focused on battling the immediate crises of hunger and joblessness.

Perkins remained committed to creating a permanent social safety net for Americans. On June 29, 1934, FDR issued an Executive Order creating a cabinet level Committee on Economic Security to prepare legislation for Congress. Its chair was Frances Perkins.

On January 15, 1935 the Committee on Economic Security presented its final report to President Roosevelt. Two days later, FDR unveiled the Social Security program and sent it to Congress.

On August 14th 1935, the president signed the Social Security Act. Later that day, the Washington Post proclaimed that the Social Security Act was the “New Deal’s Most Important Act…Its importance cannot be exaggerated …because this legislation eventually will affect the lives of every man, woman, and child in the country” (Downey 243). Secretary Perkins went on to work on other New Deal initiatives, such as the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which established a minimum wage and prohibited child labor in many workplaces.

Web Content Display

Web Content Display

Web Content Display

Web Content Display

Meanwhile, she watched Hitler’s rise in Germany with a worried eye. As things worsened in Germany, and stories broke out about increasing anti-Semitism and violence, she sought a way to help German refugees escape. Immigration laws dating back to the Coolidge administration were stringent, and many Americans feared that relaxing immigration laws would increase competition for the few jobs that were available.

Because the Immigration Service was within the Department of Labor at that time, Perskins creatively administered existing quota regulations to aid refugees in need. By 1937, her efforts “admitted 50,255 immigrants for permanent residency, two-thirds of whom were Jews and 231,884 foreign ‘visitors’” (Downey 194).

On April 12, 1945, FDR died from a sudden cerebral hemorrhage, and Harry Truman became president. Perkins and Interior Secretary Harold Ickes were the only two cabinet officials to serve for the entire 12 years of the Roosevelt administration. Although she stayed in the cabinet for Truman’s first few weeks as president, she was the first of the FDR’s holdover cabinet members to resign. She suggested to Truman that he find a “great, strong man” to fill her shoes, and Truman laughed, saying he wished she would not quit (Downey 347).

Web Content Display

Web Content Display

Web Content Display

Web Content Display

Legacy

Soon after stepping down from the cabinet, Perkins was asked to write a book about FDR’s life. The Roosevelt I Knew was the first definitive biography of the President and quickly became a bestseller (Downey 354). It remains one of the great memoirs of the Roosevelt era.

By October 1946, Perkins was back working for the Truman administration, as part of the United States Civil Service Commission, a position she held until her husband’s death in 1952. It was then that she ended her government service career, and became a lecturer at the New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University until her death in 1965 at the age of 85.

Frances Perkins would have been famous simply by being the first woman to serve in a president’s cabinet; however her involvement in the New Deal and constant fighting for the American worker makes her a legend. Although she is not well-known today, the work of Frances Perkins lives on in our unemployment insurance, minimum wage, shorter work week and federal laws regulating child labor and worker’s safety.

In commemoration of her accomplishments, in 1980 the headquarters of the United States Department of Labor in Washington, D.C. was named in her honor. Mount Holyoke College also honored her by creating the Frances Perkins Scholars, dedicated to educating women older than the usual college student.

But Frances Perkins leaves behind an even greater legacy: she helped pave the way for women to enter the male dominated political world. Twenty-one women have held cabinet positions since Frances Perkins first accepted Franklin Roosevelt’s offer to become Secretary of Labor. By accepting a position in Roosevelt’s cabinet, Frances Perkins changed the course of women’s history in America.

Citations above refer to Kirstin Downey's The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life of Frances Perkins, FDR'S Secretary of Labor and His Moral Conscience (Random House, 2009).

Web Content Display

Web Content Display

Web Content Display

Web Content Display

Suggested Reading

Frances Perkins, The Roosevelt I Knew (Viking Press, 1946).

Kirstin Downey, The Woman Behind the New Deal: The Life of Frances Perkins, FDR'S Secretary of Labor and His Moral Conscience (Random House, 2009).

David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (Oxford University Press, 1999).

Online Resources

Finding Aid to the Frances Perkins Papers at the Columbia University Libraries Archival Collections

The Frances Perkins Center in Newcastle, ME

Frances Perkins' Oral History at the Columbia University Library's Oral History Research Office

Lecture by Frances Perkins, given September 30, 1964 at Cornell University, featured as part of the online exhibit: Remembering The Triangle Factory Fire