Webcontent-Anzeige

Webcontent-Anzeige

Eleanor Roosevelt first met African American contralto opera singer Marian Anderson in 1935 when the singer was invited to perform at the White House.

Ms. Anderson had performed throughout Europe to great praise, and after the White House concert the singer focused her attentions on a lengthy concert tour of the United States. Beginning in 1936, Anderson sang an annual concert to benefit the Howard University School of Music in Washington, DC. These benefit concerts were so successful, that each year larger and larger venues had to be found.

In January 1939, Howard University petitioned the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) to use its Washington, DC auditorium called Constitution Hall for a concert to be scheduled over Easter weekend that year. Constitution Hall was built in the late 1920s to house the DAR’s national headquarters and host its annual conventions. It seated 4,000 people, and was the largest auditorium in the capital. As such, it was the center of the city’s fine arts and music events universe.

Webcontent-Anzeige

Webcontent-Anzeige

However, in 1939, Washington, DC was still a racially segregated city, and the DAR was an all-white heritage association that promoted an aggressive form of American patriotism. As part of the original funding arrangements for Constitution Hall, major donors had insisted that only whites could perform on stage.This unwritten white-performers-only policy was enforced against African American singer/actor Paul Robeson in 1930. Additionally, Blacks who attended events there were seated in a segregated section of the Hall.

The organizers of Marian Anderson’s 1939 concert hoped that Anderson’s fame and reputation would encourage the DAR to make an exception to its restrictive policy. But the request was denied anyway, and despite pressure from the press, other great artists, politicians, and a new organization called the Marian Anderson Citizens Committee (MACC), the DAR held fast and continued to deny Anderson use of the Hall.

As the controversy grew, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt carefully weighed the most effective manner to protest the DAR’s decision. Mrs. Roosevelt had been issued a DAR membership card only after the 1932 election swept her husband Franklin Roosevelt into the presidency. As such, she was not an active member of the DAR. She initially chose not to challenge the DAR directly because, as she explained, the group considered her to be “too radical” and “this situation is so bad that plenty of people will come out against it.”

Rather, Mrs. Roosevelt first led by enlightened example. She agreed to present the Spingarn Medal to Marian Anderson at the upcoming national convention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). And she invited Anderson to again perform at the White House, this time for the King and Queen of England when they came to the United States later in the year. But as the weeks went on, Mrs. Roosevelt grew increasingly frustrated that more active DAR members than she were not challenging the group’s policy.

Roosevelt Resigns from the DAR

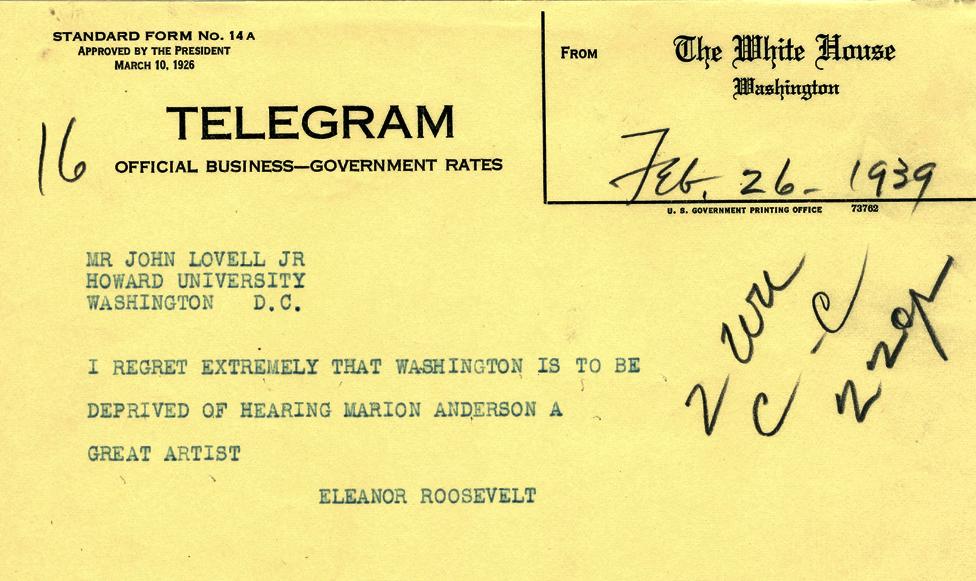

On February 26, 1939, Mrs. Roosevelt submitted her letter of resignation to the DAR president, declaring that the organization had “set an example which seems to me unfortunate” and that the DAR had “an opportunity to lead in an enlightened way” but had “failed to do so.” That same day, she sent a telegram to an officer of the Marian Anderson Citizens Committee publicly expressing for the first time her disappointment that Anderson was being denied a concert venue.

On February 27, Mrs. Roosevelt addressed the issue in her My Day column, published in newspapers across the country. Without mentioning the DAR or Anderson by name, Mrs. Roosevelt couched her decision in terms everyone could understand: whether one should resign from an organization you disagree with or remain and try to change it from within. Mrs. Roosevelt told her readers that in this situation, “To remain as a member implies approval of that action, therefore I am resigning.”

Groundbreaking 1939 Lincoln Memorial Concert

Mrs. Roosevelt’s resignation thrust the Marian Anderson concert, the DAR, and the subject of racism to the center of national attention. As word of her resignation spread, Mrs. Roosevelt and others quietly worked behind the scenes promoting the idea for an outdoor concert at the Lincoln Memorial, a symbolic site on the National Mall overseen by the Department of the Interior.

Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, himself a past president of the Chicago NAACP, was excited about such a display of democracy, and he met with President Roosevelt to obtain his approval. After the President gave his assent, Ickes announced on March 30th that Marian Anderson would perform at the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday.

Fearing that she might upstage Anderson’s triumphant moment, Mrs. Roosevelt chose not to be publicly associated with the sponsorship of the concert. Indeed, she did not even attend, citing the burdens of a nationwide lecture tour and the forthcoming birth of a grandchild. However, she and others lobbied the various radio networks to broadcast the concert to the nation.

Webcontent-Anzeige

Webcontent-Anzeige

Webcontent-Anzeige

Webcontent-Anzeige

On April 9th, seventy-five thousand people, including dignitaries and average citizens, attended the outdoor concert. It was as diverse a crowd as anyone had seen—Black, white, old, and young—dressed in their Sunday finest. Hundreds of thousands more heard the concert over the radio. After being introduced by Secretary Ickes who declared that “Genius knows no color line,” Ms. Anderson opened her concert with America. The operatic first half of the program concluded with Ave Maria. After a short intermission, she then sang a selection of spirituals familiar to the African American members of her audience. And with tears in her eyes, Marian Anderson closed the concert with an encore, Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.

The DAR’s refusal to grant Marian Anderson the use of Constitution Hall, Eleanor Roosevelt’s resignation from the DAR in protest, and the resulting concert at the Lincoln Memorial combined into a watershed moment in civil rights history, bringing national attention to the country’s color barrier as no other event had previously done.

Mrs. Roosevelt and Marian Anderson remained friends for the rest of Mrs. Roosevelt’s life. Marian Anderson continued to sing in venues around the world, including singing the National Anthem at President Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961. She died in 1993 at the age of 96.

Suggestions for further reading:

Raymond Arsenault, The Sound of Freedom: Marian Anderson, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Concert that Awakened America (Bloomsbury Press, 2009).

Allida Black, “Championing a Champion: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Marian Anderson ‘Freedom Concert’,” Presidential Studies Quarterly (Fall 1990), 719-736.