Webcontent-Anzeige

Webcontent-Anzeige

Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Thanksgiving Proclamation

At the beginning of Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency, Thanksgiving was not a fixed holiday; it was up to the President to issue a Thanksgiving Proclamation to announce what date the holiday would fall on. President Abraham Lincoln had declared Thanksgiving a national holiday on the last Thursday in November in 1863 and tradition dictated that it be celebrated on the last Thursday of that month. But this tradition was difficult to continue during the challenging times of the Great Depression as statistics showed that most people waited until after Thanksgiving to begin their holiday shopping.

Roosevelt’s first Thanksgiving in office fell on November 30, the last day of the month, because November had five Thursdays that year. This meant that there were only about 20 shopping days until Christmas; business leaders feared they would lose the much needed revenue an extra week of shopping would afford them. They asked President Roosevelt to move the holiday up from the 30th to the 23rd; however he choose to keep the Thanksgiving Holiday on the last Thursday of the month as it had been for nearly three quarters of a century.

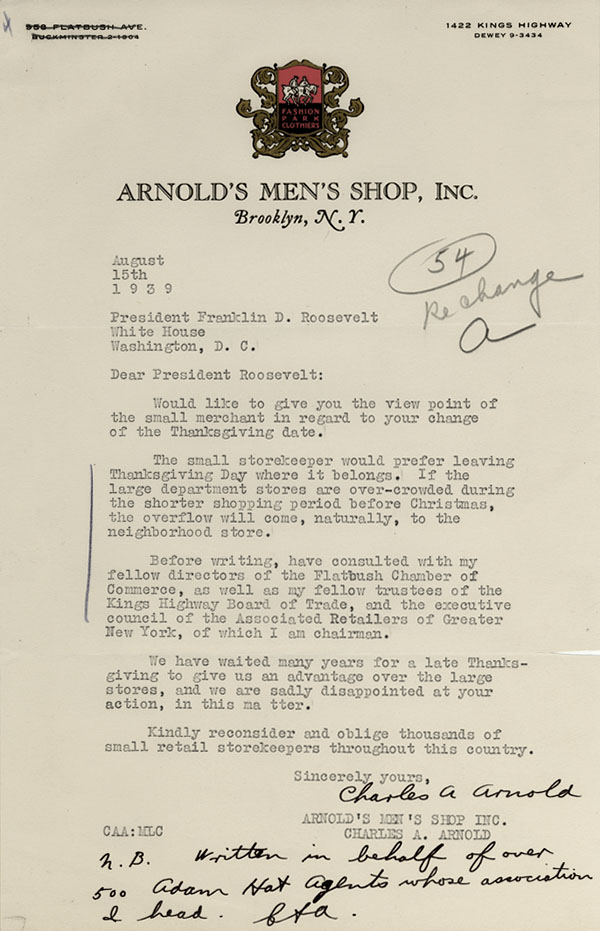

In 1939, with the country still reeling from the effects of the Great Depression, Thanksgiving once again threatened to fall on the last day of November. This time the President did move Thanksgiving up a week to the 23rd. Changing the date seemed harmless enough but it proved to be quite controversial as can be seen in this letter sent to the President in protest.

Webcontent-Anzeige

Webcontent-Anzeige

Webcontent-Anzeige

Webcontent-Anzeige

Here are some things to consider when reviewing the letter to the President:

- What does it say about our system of government that a “small merchant” feels they can write to the President and share their point of view? Why is it important for the President to hear this view?

- Compare and contrast the relationship of ‘large stores’ to neighborhood stores in 1939 and to today.

- Why do you suppose that Mr. Arnold felt compelled to mention that he had consulted with other groups before writing to the president?

- This letter gives the economic argument for opposing the change; what other arguments can be made for staying with the traditional date?

- Is this view more likely to be held by an urban shop keeper or a rural shop keeper? Why do you suppose that is the case?